Acaba de morir el dictador cubano. 57 años de falta de libertades deberían ser obituario suficiente para justificar la pertenencia de Fidel Castro al conjunto de personas que más bienestar humano han destruido en las últimas décadas.

Querría, sin embargo, escribir unas líneas para resaltar un aspecto que los apologetas del régimen algunas veces esgrimen: el comportamiento de la economía de Cuba desde 1959. Desde cualquier perspectiva que se mire, 57 años de dictadura han sido un fracaso económico sin paliativos.

Antes de entrar en materia debo resaltar que no considero que los éxitos o fracasos económicos de un sistema político hayan de ser el criterio principal de evaluación del mismo. Como dice el artículo 2 del Tratado de la Unión Europea:

“La Unión se fundamenta en los valores de respeto de la dignidad humana, libertad, democracia, igualdad, Estado de Derecho y respeto de los derechos humanos, incluidos los derechos de las personas pertenecientes a minorías. Estos valores son comunes a los Estados miembros en una sociedad caracterizada por el pluralismo, la no discriminación, la tolerancia, la justicia, la solidaridad y la igualdad entre mujeres y hombres.”

Estos son los fundamentos de la legitimidad de un régimen, en la Unión o en cualquier otro lugar del planeta.

Dado que no hay defensa alguna del comportamiento de Cuba en relación con los valores expresados en el anterior artículo (excepto el tan español y tan mediocre “¡y tu más!” mencionando las posibles peores violaciones en otros países), como explicaba antes, algunos hablan sobre los “supuestos” logros de la dictadura en términos de educación o sanidad.

Este argumento siempre me ha sorprendido. En primer lugar, porque si uno quiere seguir esa errónea ruta argumental, ¿qué hace con la España de 1954 a 1975? Entre 1954, cuando según las estimaciones más solidas, nuestra renta per capita sobrepasó su nivel anterior a la guerra civil, y 1975, el PIB español per capita en pesetas constantes (es decir, ya corregido por los cambios en los niveles de precios), se multiplicó por 3. Y no solo fue un crecimiento espectacular de la renta nacional: cualquier medida que uno mire (educación, sanidad, etc.) le dirá que entre 1954 a 1975 España pasó de ser un país pobre a ser un país relativamente rico. Desde el punto de vista económico, la España de Franco es un éxito un orden de magnitud mayor que la Cuba de Castro. Es totalmente contradictorio justificar la privación de las libertades en Cuba a cambio de una supuesta ganancia en desarrollo humano y, a la vez, no justificar con ello la dictadura en España. Todo argumento en favor de Casto gracias a sus logros económicos es, implícitamente, un argumento incluso más solido en favor de Franco.

Pero como la consistencia lógica no creo que sea un atributo que los defensores de la dictadura cubana valoren en exceso, paso directamente a la evidencia.

Empecemos con el PIB per capita. Es difícil saber cuál es el PIB per capita de Cuba, pues el régimen no ha sido nunca transparente al respecto. Por ejemplo, la Penn World Table, que es la fuente estadística más común en la literatura, no incluye a Cuba (o al menos no he podido encontrar sus datos).

El proyecto de Angus Maddison señala que el PIB per capita en Cuba en 1958 era $2363 y en 2008, el último año con datos, de $3764 (estos dólares son Geary–Khamis y por tanto intentan controlar por las diferencias en niveles de precios entre países y entre años). Esto nos da un crecimiento medio de 0.9% al año. En comparación, España pasó de $3150 en 1958 a $17734 en 2008, un crecimiento medio un pelín por debajo de 3.5% al año. Mientras que España y Cuba estaban separadas por una brecha del 33% de renta per capita en 1958, en 2008 la diferencia era el 370%. Aunque la renta per capita en España lleva estancada desde 2008 (si no ha caído una cantidad pequeña) y Cuba quizás haya crecido un poco desde 2008, el panorama es el mismo. Cuba sigue siendo un país pobre, España es una nación rica.

Podría efectuar otras comparaciones, como con Costa Rica o la República Dominicana, quizás “contrafactuales” más plausibles de una Cuba sin revolución (volveré a ello en un momento). Aunque estas comparaciones son menos contundentes, pero aun así apuntan todas ellas a la misma dirección. Por ejemplo, la República Dominicana, no muy portentoso ejemplo de casi nada, ha pasado de ser en los datos de Maddison un 45% más pobre que Cuba en 1958 a ser un 25% más rica en 2008.

Existen datos de renta per capita del Banco Mundial. Yo jamás empleo datos del Banco Mundial porque, como ya expliqué en otras entradas, los mismos sufren de problemas muy serios de corrección por niveles de precios. En esta entrada del blog Katalepsis se explica bastante bien y que concluye, de manera lapidaria:

“De 30 países [nota: 30 países de las Américas excluyendo Estados Unidos y Canadá), Cuba ocupa la posición 25, con Guatemala, Guayana, Nicaragua, Honduras y Haití por detrás.

De 12 islas caribeñas, Cuba es la número 11, sólo por delante de Haití.”

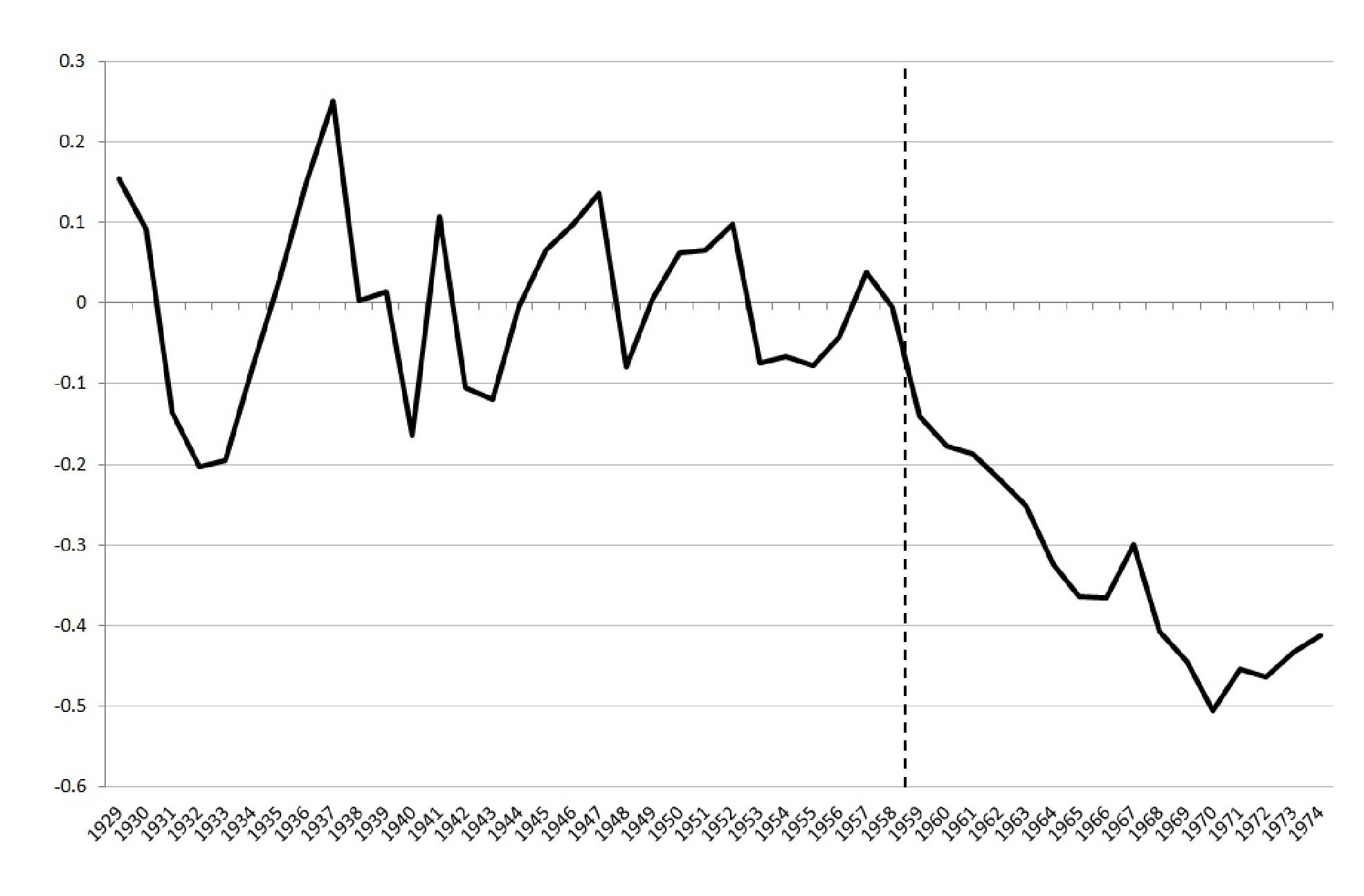

Una visión más sistemática de esta línea de razonamiento aparece en este trabajo de Felipe García Ribeiro, Guilherme Stein y Thomas Kang, en el que construyen una Cuba “sintética” sin revolución mirando a cómo otros países de la zona han crecido desde 1959 (controlando, claro, por condiciones iniciales). El gráfico 3 del trabajo, que aparece en el encabezado de esta entrada representa la diferencia entre la Cuba realmente observada y esa Cuba “sintética”. En 1974 la diferencia era ya un 40% de producto perdido (aquí otra comparación semejante).

Pero no todo es renta per capita: educación o sanidad son aspectos importantísimos de cualquier sistema económico. Pero aquí voy a “subcontratar” la explicación a un gran amigo de este blog, Pseudoerasmus, que desde Chokurdakh y con una paciencia infinita analizó hace unos años la situación de Cuba en su propio blog:

“Today, Cuba’s social metrics are marginally better than Costa Rica’s, but these were achieved at huge cost in terms of lost freedoms and lost output. But Cuba without Castro would have been at least Costa-Rica-like anyway.

The same thing for life expectancy and literacy. Cuba in 1950-60 was already more advanced in these areas than most other Latin American countries and certainly more than the Dominican Republic….

My overall point can be summarised thus. It’s not technically difficult or financially onerous to substantially improve life expectancy and infant mortality even for a poor country. What usually gets in the way is a combination of politics, institutional capacity, and cultural predispositions. Cuba’s accomplishments in human development are real, but not nearly as impressive as boosters claim. First, Cuba’s social indicators were already advanced in 1960 compared with its natural peers. Second, Castro’s regime was massively subsidised by the Soviets in overcoming the fixed costs associated with improving human development to near-developed country levels. Third, Cuba’s HD outcomes were facilitated by an authoritarian central planning regime with few political and social constraints faced by most human societies, which treated prestige health and educational metrics like Gosplan production targets to be met at all cost.”

Yo soy incluso más negativo. Cuando el dictador cubano enfermó, voló al jefe de cirugía del Gregorio Marañón. Que el dictador prefiriese a un empleado del Sistema Madrileño de Saluda sus propios médicos ya lo dice todo.

Si Cuba ha sido un desastre en términos de crecimiento económico y que la evidencia de sus países vecinos es que las mejoras en términos de desarrollo humano hubieran sido iguales o mayores en ausencia de dictadura, ¿qué explica estos malos resultados?

Aquí es donde entra la última barrera de defensa de los más ciegos defensores de la dictadura cubana. ¡La culpa es de otros! Normalmente ese otro es Estados Unidos y su embargo comercial. La verdad es que este argumento me suele dejar pasmado. Primero porque si esto fuera verdad, este sería la prueba definitiva de que el comercio internacional es maravilloso, algo que los defensores de la dictadura cubana no creo que quieran admitir, pues suelen ser ellos también los que se oponen a los acuerdos de libre comercio (aparentemente el comercio de Estados Unidos con Cuba es increíblemente beneficioso para Cuba pero el TTIP es horroroso para España; como decía antes, la consistencia lógica no parece tener mucha importancia para algunos).

Segundo, porque Cuba siempre pudo comerciar con el resto de las Américas, Europa y Asia. Aunque perder el mercado norteamericano es perjudicial, cualquier modelo de comercio internacional te va a decir que si uno puede seguir comerciando con el resto de las Américas, Europa y Asia, el coste en bienestar no va a ser mayor que unos cuantos puntos de PIB (es el mismo argumento que emplee sobre Brexit).

Tercero, porque Cuba probablemente ganó mucho más de los subsidios de la Unión Soviética con la compra de azúcar a precios inflados y la venta de petróleo a precios subsidiados (luego continuada por Venezuela) y ha seguido recibiendo grandes transferencias de capital de los emigrantes a Estados Unidos. De nuevo, este es un argumento que Pseudoerasmus explica en detalle y que no tengo que repetir.

No, no es la culpa de Estados Unidos. La dictadura cubana lo ha hecho mal económicamente porque se ha basado en un sistema, el comunismo, que siempre y en cada uno de los lugares en el que se ha aplicado ha resultado un fracaso. Al prescindir del mercado y de la propiedad privada de los medios de producción, el sistema de precios desaparece, la información necesaria para la coordinación económica se esfuma y no se generan los incentivos adecuados (a fin de cuentas, esto es de lo que va el Premio a Hart y Holmström de hace unas semanas). La dictadura cubana ha fracasado porque no podía ser de otra manera: operari sequitur esse.

El año que viene será el centenario de la revolución de octubre en Rusia (aunque en realidad de “revolución” tuvo poco; fue un golpe de estado de los que habían perdido las primeras elecciones más o menos libres en Rusia y que se negaron a aceptar el veredicto de las urnas). Lenin, un fanático sanguinario, llevó a un grupo de criminales al poder. Muchos, empezando en Cuba, siguen sufriendo las consecuencias de la caja de Pandora abierta hace casi un siglo. Hoy estamos un poco más cerca de cerrar esa caja.

P.d. Agradezco a Pseudoerasmus por señalar a la profesión muchos de los enlaces que he empleado en la escritura de esta entrada. Sin su ayuda me habría costado más del doble escribir esta entrada.

http://nadaesgratis.es/fernandez-villaverde/la-mediocridad-economica-de-la-cuba-de-castro

Comentarios leidos

Sobre el embargo, dicen en comentarios...

Cuba exporta muy poco y la mayoría de sus exportaciones son comodities que no tienen problemas para venderse (incluso a USA a traves de operaciones triangulares con Mexico u otro país) y las importaciones...pues resulta que USA esta entre sus mayores proveedores

http://atlas.media.mit.edu/.../export/usa/cub/show/2014/

El embargo mas dañino era a las inversiones, pero en Cuba esta prohibida la propiedad privada !! (ahora han abierto algo la mano) el embargo se lo hacían ellos mismos!

Jesús Fernández-Villaverde dice:

Efectivamente. Lo del embargo es un argumento que no se tiene en pie desde el punto de vista cuantitativo. Metele cualquier elasticidad de substituticion medianamente razonable a las importaciones desde Estados Unidos con respecto a las de Alemania o Japon, unos costes de transporte medianamente normales y que te sale? Mucho menos que el valor de la ayuda sovietica por décadas.

http://atlas.media.mit.edu/.../export/usa/cub/show/2014/

El embargo mas dañino era a las inversiones, pero en Cuba esta prohibida la propiedad privada !! (ahora han abierto algo la mano) el embargo se lo hacían ellos mismos!

Jesús Fernández-Villaverde dice:

Efectivamente. Lo del embargo es un argumento que no se tiene en pie desde el punto de vista cuantitativo. Metele cualquier elasticidad de substituticion medianamente razonable a las importaciones desde Estados Unidos con respecto a las de Alemania o Japon, unos costes de transporte medianamente normales y que te sale? Mucho menos que el valor de la ayuda sovietica por décadas.

Esta es la definicion de bloqueo en derecho internacional

http://opil.ouplaw.com/.../9780199.../law-9780199231690-e252

"A blockade is a belligerent operation to prevent vessels and/or aircraft of all nations, enemy and neutral (Neutrality in Naval Warfare), from entering or exiting specified ports, airports, or coastal areas belonging to, occupied by, or under the control of an enemy nation. The purpose of establishing a blockade is to deny the enemy the use of enemy and neutral vessels or aircraft to transport personnel and goods to or from enemy territory (Transit of Goods over Foreign Territory). In view of its impact on the commercial relations between the blockaded belligerent and neutrals, a blockade is regularly considered a method of economic warfare, and thus dealt with in the context of the law of neutrality."

Cuando un regimen tiene que mentir hasta en lo que dice que le hace Estados Unidos (desde el 20 de Noviembre de 1962, cuando concluyo la crisis de los misiles,

http://opil.ouplaw.com/.../9780199.../law-9780199231690-e252

"A blockade is a belligerent operation to prevent vessels and/or aircraft of all nations, enemy and neutral (Neutrality in Naval Warfare), from entering or exiting specified ports, airports, or coastal areas belonging to, occupied by, or under the control of an enemy nation. The purpose of establishing a blockade is to deny the enemy the use of enemy and neutral vessels or aircraft to transport personnel and goods to or from enemy territory (Transit of Goods over Foreign Territory). In view of its impact on the commercial relations between the blockaded belligerent and neutrals, a blockade is regularly considered a method of economic warfare, and thus dealt with in the context of the law of neutrality."

Cuando un regimen tiene que mentir hasta en lo que dice que le hace Estados Unidos (desde el 20 de Noviembre de 1962, cuando concluyo la crisis de los misiles,

http://atlas.media.mit.edu/es/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/usa/cub/show/2014/

Otra es sobre las "cifras" que entran en el computo del Indice de desarrollo humano de Cuba. Pseudoerasmus discute varios de estos temas, pero este articulo que enlaza que reproduce es demoledor:

“Cuba does have a very low infant mortality rate, but pregnant women are treated with very authoritarian tactics to maintain these favorable statistics,” said Tassie Katherine Hirschfeld, the chair of the department of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma who spent nine months living in Cuba to study the nation’s health system. “They are pressured to undergo abortions that they may not want if prenatal screening detects fetal abnormalities. If pregnant women develop complications, they are placed in ‘Casas de Maternidad’ for monitoring, even if they would prefer to be at home. Individual doctors are pressured by their superiors to reach certain statistical targets. If there is a spike in infant mortality in a certain district, doctors may be fired. There is pressure to falsify statistics...

Hirschfeld said she’s "a little skeptical" about the longevity data too, since Cuba has so many risk factors that cause early death in other countries, from unfiltered cigarettes to contaminated water to a meat-heavy diet. In a more benign statistical quirk, Carmelo Mesa-Lago, a professor emeritus of economics at the University of Pittsburgh, suggests that the flow of refugees could skew longevity statistics, since those births are recorded but the deaths are not.

Transparency would help give the data more credibility, but the Cuban government doesn’t offer much, experts said.

"I would take all Cuban health statistics with a grain of salt," Hirschfeld said. Organizations like the Pan-American Health Organization "rely on national self-reports for data, and Cuba does not allow independent verification of its health claims."”

Por supuesto. Y es por ello que en este blog defendemos los principios del articulo 2 del TUE, como base de un sistema politico, y una politica economica, basada en la economia de mercado y un estado del bienestar, que genere prosperidad paratodos.

Estos dias se nos olvida a menudo, pero las sociedades mas decentes que los seres humanos hemos creado se han basado siempre en el estado de derecho, la democracia representativa, la economia de mercado y un estado del bienestar en el contexto de un marco de derecho internacional de resolucion pacifica de las disputas. Bien gestionadas, estas sociedades y el marco "liberal" internacional son la mejor barrera contra Lenin y Hitlers. "JFV

The paradox of Cuban GDP

The calculation of Cuban GDP is, surprisingly, a contentious issue. There are those who say that Cuba is one of the richest countries of Latin America, and there are those who say that the Cuban economy is mediocre. Who is right, and what causes this divergence?

Let’s look at Cuban GDP per capita according to the World Bank.

According to this measure, Cuba would have a GDP per capita in 2000 constant dollars of about 5400$. This places Cuba into the ‘middle class’ of Southamerica: below rich countries (Puerto Rico, Aruba, and Las Bahamas have 4x GDPpc), but above countries like Haiti, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Guatemala, Jamaica, or Colombia.

In order to be able to compare datapoints within a given timeseries for a given country, constant dollars GDP takes inflation into account. Now, to compare different countries, their GDP expressed in their national currencies is converted to a common currency: dollars.

This, however, doesn’t take into account the fact that prices in each country are different. That’s why another correction is applied: adjusting for Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). World Bank also has PPP adjusted GDP per capita data.

According to this series of data, Cuba is now above many more countries, only bested by the Cayman Islands, Aruba, Trinidad y Tobago, Las Bahamas, Chile, St. Kitts y Nevis, and Antigua y Barbuda. Cuba would be the 9th richest country out of 37, something much more impressive.

The paradox arises when one reads the Maddison Project GDP data, that tries to produce historically comparable GDP series for many different countries. Instead of PPP adjusted constant dollars, they use international (Geary-Khamis) constant dollars (1990), which is also PPP adjusted, but in a different way.

By this measure, Cuba is again a poor country within Latin America, both in an absolute and relative sense, compared to 1960.

If we look at Cuba by periods:

The first period (first blue rectangle) starts after the end of the Cuban Revolution, marked by stagnation in economic growth.

The second period starts with Cuba joining the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), an international cooperation organisation promoted by the USSR. Cuba received substantial subsidies from COMECON, including sugar purchases – Cuba’s top export – at prices 11 times market prices. With Soviet help, Cuba experiences strong rates of growth.

The third period is the so called Special Period that started with the end of Soviet subsidies, which implied a need to readapt the economy. At the same time, the government implemented reforms that opened somewhat the economy to the outside, supporting tourism. These measures have some success, relaunching Cuba’s economy.

So we now pose and solve our question: What is actually Cuba’s GDP’ Why do the World Bank and Maddison give different estimates?

According to Bolt & van Zanden (2013), in the methodological notes of Maddison’s data, there are difficulties estimating what PPP index to apply to Cuba. They explain how they tried to overcome them. This is our first lead: that the issue lies in estimating PPP indices.

Cuba, 1800-1902, Santamaría, A. (2005), ‘Las cuentas nacionales de Cuba, 1690–2005’ Centro de Estudios Históricos, Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (mimeo). The level for 1800 assumed to be identical to that for 1792. 1902-1958, Ward, M. and J. Devereux (2009), “The Road Not Taken: Pre-Revolutionary Cuban Living Standards in Comparative Perspective” (mimeo) 1958 onwards, Maddison, A. (2009), Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1- 2006 AD, last update: March 2009, horizontal file http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/. An important caveat is that Maddison (2006) level for 1990 has not been accepted. The reason is that given the lack of PPPs for Cuba in 1990 Maddison (2006: 192) assumed its per capita GDP was 15 percent below the Latin American average. Since this is an arbitrary assumption, I started from Brundenius and Zimbalist’s (1989) estimate of Cuba’s GDP per head relative to six major Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela, LA6) in 1980 (provided in Astorga and Fitzgerald 1998) and applied this ratio to the average per capita income of LA6 in 1980 Geary-Khamis dollars to derive Cuba’s level in 1980. Then, following Maddison (1995: 166), I derived the level for 1990 with the growth rate of real per capita GDP at national prices over 1980-1990 and reflated the result with the US implicit GDP deflator to arrive to an estimate of per capita GDP in 1990 at 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars. Interestingly the position of Cuba relative to the US in 1929 and 1955 is very close to the one Ward and Devereux (2009) derived with a different approach. (Bolt & van Zanden 2013)

In turn, in another paper, Ward and Devereux (2009) apply a different method, the Ideal Fisher Index .

The Penn World Tables (the PWT) and Maddison (2007) value income with world prices calculated using the Geary Khamis procedure. In simple terms, Geary Khamis world prices are the expenditure-weighted average of national prices for all economies. We lack sufficient data to calculate Geary Khamis price indices for Cuba. For our bilateral comparison, the Fisher Ideal index has theoretical advantages over the Geary Khamis index. In particular, it is a “superlative index” and does not suffer from a substitution bias arising from using a fixed set of world prices see Diewert (1976), see also Neary (2004).

These two methods (Geary-Khamis dollars and the IFI) so far coincide in their results.

But then what does the World Bank do? The same thing that the Penn World Tables (PWT, another source for macroeconomic data) used to do: Use the price indices from the Interntional Comparison (price) Program from the World Bank. And it turns out that some authors who participated in the production of the PWT have criticised the 2005 version of the price indices, which is why Cuban GDP is not in the PWT anymore.

The World Bank has slowly realised that there is something wrong with Cuban GDP, and in the latest revision of their price indices, there isn’t even an estimate of Cuban GDP, saying that

The official GDP of Cuba for reference year 2011 is 68,990.15 million in national currency. However, this number and its breakdown into main aggregates are not shown in the tables because of methodological comparability issues. Therefore, Cuba’s results are provided only for the PPP and price level index. In addition, Cuba’s figures are not included in the Latin America and world totals.

If the economistS in charge of PWT, and the ones at WB doubt their own estimates for PPP adjusted Cuban GDP, it is hard to take them as valid. Maddison’s and Ward-Devereux’s, on the other hand, do give similar results, which may indicate that they are closer to the truth.

Yet another source that we can use is UNDP, the UN agency that produces the Human Development Indices. In a 2010 report, they also express doubts regarding the calculation of Cuban GDP. But in their 2015 report, using a revised GDP, they do provide an estimate, and this times it is closer to the values of Maddison and W-D. Using this corrected GDP, by the way, their HDI falls to 0.759, and so Cuba drops from the second country with the highest HDI in Latin America to being the ninth.

The 2013 HDI value published in the 2014 Human Development Report was based on miscalculated GNI per capita in 2011 PPP dollars, as published in the World Bank (2014). A more realistic value, based on the model developed by HDRO and verified and accepted by Cuba’s National Statistics Office, is $7,222. The corresponding 2013 HDI value is 0.759 and the rank is 69th.

So finally, with the per capita GNP data (Not GDP, but this is not relevant) from UNDP (2011 dollars, PPP adjusted), Latin American countries can be ranked like this:

| Trinidad and Tobago | 26.090 |

| Argentina | 22.050 |

| Bahamas | 21.336 |

| Chile | 21.290 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 20.805 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 20.070 |

| Uruguay | 19.283 |

| Panama | 18.192 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 16.159 |

| Mexico | 16.056 |

| Brazil | 15.175 |

| Costa Rica | 13.413 |

| Barbados | 12.488 |

| Colombia | 12.040 |

| Dominican Republic | 11.883 |

| Peru | 11.015 |

| Grenada | 10.939 |

| Ecuador | 10.605 |

| Dominica | 9.994 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 9.937 |

| Saint Lucia | 9.765 |

| Paraguay | 7.643 |

| Jamaica | 7.415 |

| El Salvador | 7.349 |

Cuba | 7.301 |

| Guatemala | 6.929 |

| Guyana | 6.522 |

| Nicaragua | 4.457 |

| Honduras | 3.938 |

| Haiti | 1.669 |

Out of 30 countries, Cuba is the 25th, with Guatemala, Guayana, Nicaragua, Honduras y Haiti behind.

Out of 12 Caribbean islands, Cuba is the 11th, with only Haiti behind.

Conclusion

On the one hand, we have World Bank’s estimate, that WB itself doubts. On the other hand, we have estimates from Ward-Devereux, Maddison, and UNCP. These three sources seem to approximately coincide on what the actual Cuba GDP is. This triple coincidence, versus the questionable values from WB, would make us choose the former values, and so accept that Cuba is a poor country within Latin America.

One critique to this would be to compare Cuba using other indicators: mortality, life expectancy, literacy rate, or malnutrition. This is also interesting, but not the point of this post.

The paradox of Cuban GDP is thus solved.

https://artir.wordpress.com/2016/11/30/the-paradox-of-cuban-gdp/

Ideology & Human Development

How real are Cuba’s accomplishments in health and education since the revolution? How do they compare with the situation prior to the revolution? Was the Soviet Union’s subsidy to Cuba crucial to its human development? Did the US hostility to the Cuban Revolution have an impact?

{ Edit-Addendum 26 Nov. 2016: This blogpost was written 2.5 years ago as a rejoinder to with commenter Matt in a debate about human development in Cuba as well as Kerala, China, South Korea, West Bengal, etc. So it may make references not immediately obvious from the context. See Debate with Matt. }

Years ago some astute person noted that I was a hypocrite for being centre-left in the context of discussing political economy in developed countries, but rather centre-right when it came to the Third World. He was right, except that it’s not hypocritical. In already-rich countries with already-efficient economies, the levels of income redistribution that are in political play are typically not so great as to endanger efficiency. The productivity of the core OECD economies is high enough that social democracy is fundamentally affordable. One can think of Germany, for example, as being able to manage a strong welfare state despite a low labour force participation rate (compared with the United States), because German output per hour is so high.

However, there’s a much greater trade-off between economic efficiency and income redistribution in poorer countries. In the moderate scenario you have a case like the macroeconomic populism of Argentina under Peronism, where consumption transfers to the public were financed by budget deficits and money printing. In the extreme, a variety of Marxist-Leninist regimes expropriated, controlled, and managed all productive assets. But most of those regimes did divert national resources toward ending mass poverty and toward healthcare and education. Thus, under communist rule, the Soviet Union, its Eastern European satellites, Mongolia, the People’s Republic of China, and Cuba achieved better outcomes in literacy, infant mortality, life expectancy, and years of schooling than countries with comparable levels of per capita income.

In most of these countries, the human development might have occurred under capitalism anyway, but probably with a delay. So they sacrificed higher incomes in the long run for the immediate alleviation of poverty. However, since the sample of countries that have been governed by Marxist regimes for any length of time under conditions of peace and stability is quite small, we really don’t know whether this “human development” pattern is a general tendency of actually-existed Marxist regimes, or merely a cultural characteristic of those particular societies. With the exception of Cuba, they are all European or East Asian. (Yes, I’m aware there were other Marxist regimes, but their lifespans were much shorter and/or they were embroiled in war.)

There was a time when I entertained the idea that the poorest countries were so inept at capitalist economic development that most of them might actually be better off under a totalitarian redistributionist regime. But I don’t think that any more, because even when it comes to central planning socialism some countries are just less good at it than others. Administrative competence varies.

Nonetheless, the fact that mass poverty persists lead some left-wing observers to question the moral difference between democratic capitalism and something as extreme as Maoism. For example, Noam Chomsky made the case in his column on The Black Book of Communism that India killed even more people than Maoist China, just more slowly and less visibly :

Like others, Ryan reasonably selects as Exhibit A of the criminal indictment the Chinese famines of 1958-61, with a death toll of 25-40 million…. The terrible atrocity fully merits the harsh condemnation it has received for many years, renewed here. It is, furthermore, proper to attribute the famine to Communism. That conclusion was established most authoritatively in the work of economist Amartya Sen, whose comparison of the Chinese famine to the record of democratic India received particular attention when he won the Nobel Prize a few years ago. Writing in the early 1980s, Sen observed that India had suffered no such famine. He attributed the India-China difference to India’s “political system of adversarial journalism and opposition,” while in contrast, China’s totalitarian regime suffered from “misinformation” that undercut a serious response, and there was “little political pressure” from opposition groups and an informed public (Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen, Hunger and Public Action, 1989; they estimate deaths at 16.5 to 29.5 million).

The example stands as a dramatic “criminal indictment” of totalitarian Communism, exactly as Ryan writes. But before closing the book on the indictment we might want to turn to the other half of Sen’s India-China comparison, which somehow never seems to surface despite the emphasis Sen placed on it. He observes that India and China had “similarities that were quite striking” when development planning began 50 years ago, including death rates. “But there is little doubt that as far as morbidity, mortality and longevity are concerned, China has a large and decisive lead over India” (in education and other social indicators as well). He estimates the excess of mortality in India over China to be close to 4 million a year: “India seems to manage to fill its cupboard with more skeletons every eight years than China put there in its years of shame,” 1958-1961 (Dreze and Sen).

In both cases, the outcomes have to do with the “ideological predispositions” of the political systems: for China, relatively equitable distribution of medical resources, including rural health services, and public distribution of food, all lacking in India. This was before 1979, when “the downward trend in mortality [in China] has been at least halted, and possibly reversed,” thanks to the market reforms instituted that year.

Overcoming amnesia, suppose we now apply the methodology of the Black Book and its reviewers to the full story, not just the doctrinally acceptable half. We therefore conclude that in India the democratic capitalist “experiment” since 1947 has caused more deaths than in the entire history of the “colossal, wholly failed…experiment” of Communism everywhere since 1917: over 100 million deaths by 1979, tens of millions more since, in India alone.

Thus, for Chomsky, the social inequities of capitalism in the Third World — regardless of whether they are caused by capitalism or merely tolerated under the system — are so evil that any political programme which does not redistribute wealth for the immediate remedy of these inequities is as lethal as the worst excesses of Stalinism or Maoism.

For many on the left, the “human development” accomplishments and aspirations of the old socialist states like Cuba still compare favourably with the evils of capitalist development in the Third World.

But are Cuban accomplishments real and impressive?

Life Expectancy

I argued that since the Cuban government has total command of all resources on the island and marshals them without democratic constraint, Cuba’s HDI score is not all that impressively greater than the Dominican Republic’s. Matt replies I understate the disparity :

“…if we look at non-income HDI (which we should be able to, given that Cuba’s and DR’s per capita GDPs are comparable), we find that Cuba’s is 0.894 and DR’s is 0.726, a difference of 0.168. Cuba not only does much better than DR on this measure, it actually scores within the same range as the UK (0.886) and Hong Kong (0.907), despite far lower per capita income.”

The “Human Development Index”, which is generated by the United Nations Development Programme as a way of capturing human welfare and living standards which are only imperfectly measured by GDP, is a composite score of per capita income, educational attainment, and life expectancy. Non-income HDI is therefore simply a composite of life expectancy and educational attainment, which I will examine separately.

First, an empirical note about life expectancy: the relationship between GDP per capita and life expectancy is approximated by the Preston curve :

For low incomes, increasing income can lead to hefty gains in life expectancy, but as income gets higher the “returns” to income diminish. Yet, at the same time, there’s a pretty large variation in life expectancy values even for fairly low levels of per capita income. So countries such as Mexico, Syria, Honduras, and Bangladesh have values in the 70s. In other words, it’s not that onerous, in terms of income requirement, to raise life expectancy to within 10 years of the richest countries in the world. Quite apart from simply having more food to eat, the job can be done by fairly low-cost public health measures that raise micronutrient intake, inoculate populations, and improve sanitary standards (e.g., relating to water and sewage). Which is why life expectancy at birth has grown more steadily than per capita income in the developing countries :

(Sorry it’s in French, I could not find a comparably detailed time series by region in English.)

So, at first approximation at least, it’s a matter of politics, whether societies choose to make those relatively inexpensive outlays to improve the conditions that prolong life. (Africa’s progress has been depressed by AIDS, particularly in southern Africa.) Of course it requires a certain amount of administrative competence and social cohesion in order to implement basic public health measures in the first place. These capacities are not uniformly distributed in the world. But what ever the causes of the global variation in institutional capacity and administrative competence, they are clearly very difficult to modify if there is a vicious circle, a stable equilibrium, of bad institutions => low growth, low human development => bad institutions, etc.

Infant Mortality

The World Bank data peg Cuba’s and the Dominican Republic’s life expectancy at 79 and 73, respectively. According to UNSTAT, life expectancy at 60 is roughly the same for Cuba and the Dominican Republic. This implies that most of the difference in their average population longevities is due to their differences in neonatal and under-five mortality.

During the Middle Ages, childhood was the most dangerous period in a person’s life, but once you survived it, you generally could expect a fairly long life. Likewise, the epidemiological difference between a developing and a developed country is that there is a high probability of dying of childhood and communicable diseases in the poorer country, than in the richer country where there is a high likelihood of dying from the noncommunicable diseases of old age and affluence, such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes.

Wikipedia has UNSTAT’s data for infant mortality (neonatal) spanning over six decades. The World Bank has the U5 child mortality rates over a similar period. Cuba’s infant mortality rate of 5-6 per 1000 live births is not quite as low as the range seen in the developed countries (2-4), but fairly close. Thus, mortality in Cuba very much mirrors the developed world pattern: most people die of the diseases of old age. The Dominican Republic’s neonatal mortality, however, is in the range of 25-30 per 1000 live births.

Now, I had already said “I have no problem with the view that, all else equal…, a redistributionist political regime in a poor country is more likely to improve HDI than a non-redistributionist one”. Clearly, Cuba has put a large share of its scanty resources into prenatal and postnatal care, whilst the Dominican Republic has not done to the same degree. Matt finds it “remarkable” that Cuba has achieved this (along with other things) despite numerous obstacles. But I’m not so impressed.

First, as I’ve already argued, it’s not very expensive and it’s not technically difficult to improve such indicators as life expectancy and infant mortality. It’s largely a matter of importing technology and getting one’s administrative act together, given the political desire to do so. And compared with most developing countries with their institutional deficiencies, a central planning dictatorship with exclusive control over resources and without traditional constraints can probably exercise more brute administrative competence. (More on this below.)

Second, it was inherently easier for Cuba to lower its infant mortality rate than for the Dominican Republic. Why? Because it was already lower for Cuba in 1950 and 1960, than in most of the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean. Look at the UNSTAT data. Cuba’s infant mortality rates in 1950-55 and 1955-60 were well below the average/median for Latin American and the Caribbean. In fact, only Uruguay, Puerto Rico, Argentina and various non-Hispanophone Caribbean countries beat Cuba in this regard. The Dominican Republic was about average for the region. (But the Latin American country in 2012 that’s most improved relative to its rank in 1950, would appear to be Chile.)

The same thing for life expectancy and literacy. Cuba in 1950-60 was already more advanced in these areas than most other Latin American countries and certainly more than the Dominican Republic.

Another way to look at it: today, Cuba’s social metrics are marginally better than Costa Rica’s, but these were achieved at huge cost in terms of lost output and lost freedoms. But Cuba without Castro would have been at least Costa-Rica-like anyway.

The Production of Cuban Health

The Soviet production system was famously wasteful. Resources (energy, raw materials, labour, machine-time etc.) were used to generate a unit of output which was relatively undesirable or maybe even worth less than the inputs. For example, the Soviets harvested Kamchatka crab but their canneries converted them into dogdy tins of semi-preserved arthropodic matter, along with a lot of “leakage”. That’s why ultimately the Soviets could not afford their system; at some point you just can’t throw more and more resources to salvage your production targets.

Input-ouput issues also matter in healthcare. Cuba’s health-related finances are opaque, but there’s one simple proxy for the amount of resources the Cubans have thrown at producing their health outcomes: physicians per 1000 population. It’s astronomical! 6.7 per 1000 is the second highest in the world and is astounding by any standard, let alone for a poor country like Cuba. Most rich countries have 3-4 per 1000. I’ve also read that Cuba has the highest doctor-patient ratio in the world, but I can’t find a proper citation (as opposed to a bunch of rubbish sites saying it). People think this is a good thing, but it is not. It’s clearly a misallocation of resources, just like those Soviet tinned crabs.

Maybe we shouldn’t be talking about productivity when it comes to saving the life of the extra infant or two per 1000. Perhaps, but the issue speaks to how “impressive” the achievement really is. No normal society with a market economy, even with a large welfare state and nationalised healthcare system, would allocate so many resources to producing so many doctors. And short of authoritarian central planning socialism it probably could never happen, especially in most developing countries with weak institutions. Just think of Pakistan, where mobile health workers offering child vaccinations meet resistance from parents or are terrorised by religious fanatics. Cuba’s health outcomes almost certainly require intrusive, authoritarian measures.

There’s a lot of propaganda and misinformation about Cuba, on both left and right, so I’m wary of available sources. But this article cites anthropologist Katherine Hirschfeld, author of this book which I have read and found reliable :

“Cuba does have a very low infant mortality rate, but pregnant women are treated with very authoritarian tactics to maintain these favorable statistics,” said Tassie Katherine Hirschfeld, the chair of the department of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma who spent nine months living in Cuba to study the nation’s health system. “They are pressured to undergo abortions that they may not want if prenatal screening detects fetal abnormalities. If pregnant women develop complications, they are placed in ‘Casas de Maternidad’ for monitoring, even if they would prefer to be at home. Individual doctors are pressured by their superiors to reach certain statistical targets. If there is a spike in infant mortality in a certain district, doctors may be fired. There is pressure to falsify statistics.”

I find the above credible because Cuba has one of the highest reported abortion rates in the world. (Most communist or ex-communist countries are above average.) The link is to a publication associated with Planned Parenthood, so I think it’s not biased against Cuba or abortions. It’s also believable because, for Cuba, health has become what Olympic gold medals had been to the East bloc: an international badge of prestige to showcase the achievements of socialism. So while I do believe the official health data are probably accurate, it’s likely draconian means are used and material deprivations are exacted on the populace, in order to achieve or maintain those outcomes.

Cuba’s “Obstacles”

Matt has cited numerous “obstacles” in the way of Cuba’s achieving human development outcomes. These include :

- the US trade embargo against Cuba ;

- the loss of Soviet foreign aid after 1990 ;

- high military expenditure on the part of Cuba, made necessary by unremitting “terrorism directed from Miami and Langley”

- the flight of a large number of educated Cubans to the United States after 1960

I argued that the US trade embargo against Cuba was more than offset by a combination of Soviet subsidies and trade with other countries. Cuba sold sugar to the Soviet Union at a loss relative to the world price during the 1960s, but in the 1970s the Soviet price was more than a third above the world price. By the late 1980s the Soviet subsidy to Cuba implicit in the official price of sugar was 11 times the world price. [Source]

Matt has countered that Cuba lost this sugar daddy 23 years ago. That’s true, but he fails to consider that the fixed costs of investment in schools, universities, hospitals, sugar-refineries, disease eradication, etc. are front-loaded. Even those skilled Cubans who received their education in the late 1980s are still only at the mid-point of their working age. Likewise, if the Castro regime mostly eliminated dengue fever through the use of pesticides and water management, that continues to produce health returns today.

Besides, Cuban GDP per capita began its slow recovery in 1993 and reverted to the 1990 level by 2005. This was caused by a combination of tourist receipts, increased remittances from Cuban-Americans, barter trade with Venezuela, foreign investment, and debt accumulation with European and Japanese banks. Despite the embargo, US financial flows to Cuba were sizeable in the 1990s and are today the largest single source of foreign currency for Cuba.

Matt has argued Cuba’s human development spending was all the more impressive because US hostility required Castro to spend so much money on the military. But Castro’s adventurism in Africa in the 1970s totally belies the claim that its military expenditure was fundamentally defensive.

Angola was a real war for Cuba, with actual military operations conducted by up to 35,000 troops against South African forces in 1975-76 and 55,000 troops in 1987-88. [Source : Castro’s own words.] The total number of Cubans who ever served in Angola in 1975-1991 is on the order of 400,000. [Source, page 146.] Nearly 20,000 Cuban combat and support troops also saw action in the Ogaden War between Ethiopia and Somalia. I reproduce the following from Porter :

All of the above was luxury consumption for Castro. Nothing forced him to divert resources away from human development toward adventurism in Africa.

Cuban education

One half of the non-income HDI composite is just years of schooling. That doesn’t really tell us anything about how Cuban students actually perform in comparison with other countries, and Cuba doesn’t participate in PISA. But its students do take the SERCE exams administered by UNESCO. Here are the results :

Amazing! Cuba’s score in each category is more than 1 standard deviation above the mean. If the above scores are representative of these countries’s students, then, according to these calculations, that implies Cuba’s IQ would be 2 std above Ecuador’s and the Dominican Republic’s, and at least 1 std above Cuban-Americans — the very group Matt has claimed is disproportionately comprised of the pre-revolutionary elite. If that’s true, then Cuban teachers have accomplished something that no one else, anywhere else, has ever done. ¡Viva la Revolución!

Or, another possibility is suggested by this chart from the same SERCE report :

Apparently an assistant forgot to tell the Cuban minister of education that schools must not perform the academic equivalent of electing a president with 99.9% of the vote. What do American education researchers call it? Creaming ? Another potential term: Potemkin schools.

Matt argues that an additional handicap for Cuba was the emigration of at least 10% of the country’s population who were disproportionately skilled and educated. The Dominican Republic, he contrasts, emitted less skilled immigrants to the United States. Here are the educational characteristics of Cuban-Americans and Dominican-Americans :

Ideally, these cohorts should be matched by various characteristics, such as age and generation, and that’s possible through data from the Census Bureau and the American Community Survey, but Matt will have to pay me to do it. All the same, Cubans who actually left Cuba do not look particularly more elite than Dominican-Americans. Native-born Cuban-Americans look better educated, but not by so much. It only makes sense: there were three major waves of Cuban emigration, and most of the skilled and educated were concentrated in the first wave whereas the last wave (the Mariel) were clearly the opposite of the upper stratum.

Edit-addendum (26 Nov 2016): For some reason this post is getting a lot of traffic this week… Since posting this two and half years ago, I have read Carnoy’s Cuba’s Academic Advantage, which tries to explain Cuba’s extraordinary results in SERCE. Unfortunately its point of departure is that Cuba’s results are real and representative and does not question it. This is more or less all that Carnoy has to say about it:

Even by Carnoy’s own description of the Cuban education system, it is tightly controlled, authoritarian, and centralised. So, in the face of strong incentives to treat education and healthcare as internationally prestigious projects, kind of like the Olympics; and in light of the extraordinary SERCE results, scepticism about them is justified and we need more than UNESCO assurances.

Originally I did not mention urban-rural disparity. I’m predisposed to believe Cuban results would show a smaller difference between urban and rural areas than most other Latin America. But this is quite amazing and another cause for scepticism:

{End edit}

Conclusion

My overall point can be summarised thus. It’s not technically difficult or financially onerous to substantially improve life expectancy and infant mortality even for a poor country. What usually gets in the way is a combination of politics, institutional capacity, and cultural predispositions. Cuba’s accomplishments in human development are real, but not nearly as impressive as boosters claim. First, its social indicators were already advanced in 1960 compared with its natural peers. Second, Castro’s regime was massively subsidised by the Soviets in overcoming the fixed costs associated with improving human development to near-developed country levels. Third, Cuba’s social development outcomes were facilitated by an authoritarian central planning regime with few political and social constraints faced by most human societies. Cuban doctors and educators treat health and educational metrics like Gosplan production targets to be met at all cost. The Cuban government allocates resources to health and education by severely restricting consumption elsewhere and reducing overall welfare.

Mi punto general puede resumirse de este modo. No es técnicamente difícil o económicamente onerosa para mejorar sustancialmente la esperanza de vida y la mortalidad infantil, incluso para un país pobre. Lo que generalmente se interpone en el camino es una combinación de la política, la capacidad institucional, y predisposiciones culturales. Los logros de Cuba en el desarrollo humano son reales, pero no es tan impresionante como afirman impulsores. En primer lugar, sus indicadores sociales que ya se avanzaron en el año 1960 en comparación con sus pares naturales. En segundo lugar, el régimen de Castro fue masivamente subvencionado por la Unión Soviética en la superación de los costes fijos asociados a la mejora del desarrollo humano a nivel de los países desarrollados-cerca. En tercer lugar, los resultados de desarrollo social de Cuba fueron facilitadas por un régimen autoritario de planificación central con muy pocas restricciones políticas y sociales que enfrenta la mayoría de las sociedades humanas.médicos y educadores cubanos tratan de salud y educativos métricas como los objetivos de producción Gosplan que deben cumplir a toda costa. El gobierno cubano asigna recursos para la salud y la educación al restringir severamente el consumo en otro lugar y reducir el bienestar general.

https://pseudoerasmus.com/2014/06/25/human-development/

A favor

http://blogs.elconfidencial.com/economia/grafico-de-la-semana/2016-11-30/legado-economico-fidel-castro_1297069/

Los errores de una economia planificada el caso Zafra

http://articulosclaves.blogspot.com.es/2016/11/cuba-empieza-la-transicion-superara-los.html

A favor

http://blogs.elconfidencial.com/economia/grafico-de-la-semana/2016-11-30/legado-economico-fidel-castro_1297069/

Los errores de una economia planificada el caso Zafra

http://articulosclaves.blogspot.com.es/2016/11/cuba-empieza-la-transicion-superara-los.html