German budget surpluses are bad for the global economy

ON AUGUST 24th Germans received news to warm any Teutonic heart. Figures revealed a larger-than-expected budget surplus in the first half of 2016, and put Germany on track for its third year in a row in the black. To many such excess seems harmless enough—admirable even. Were Greece half as fiscally responsible as Germany, it might not be facing its eighth year of economic contraction in a decade. Yet German saving and Greek suffering are two sides of the same coin. Seemingly prudent budgeting in economies like Germany’s produce dangerous strains globally. The pressure may yet be the undoing of the euro area.

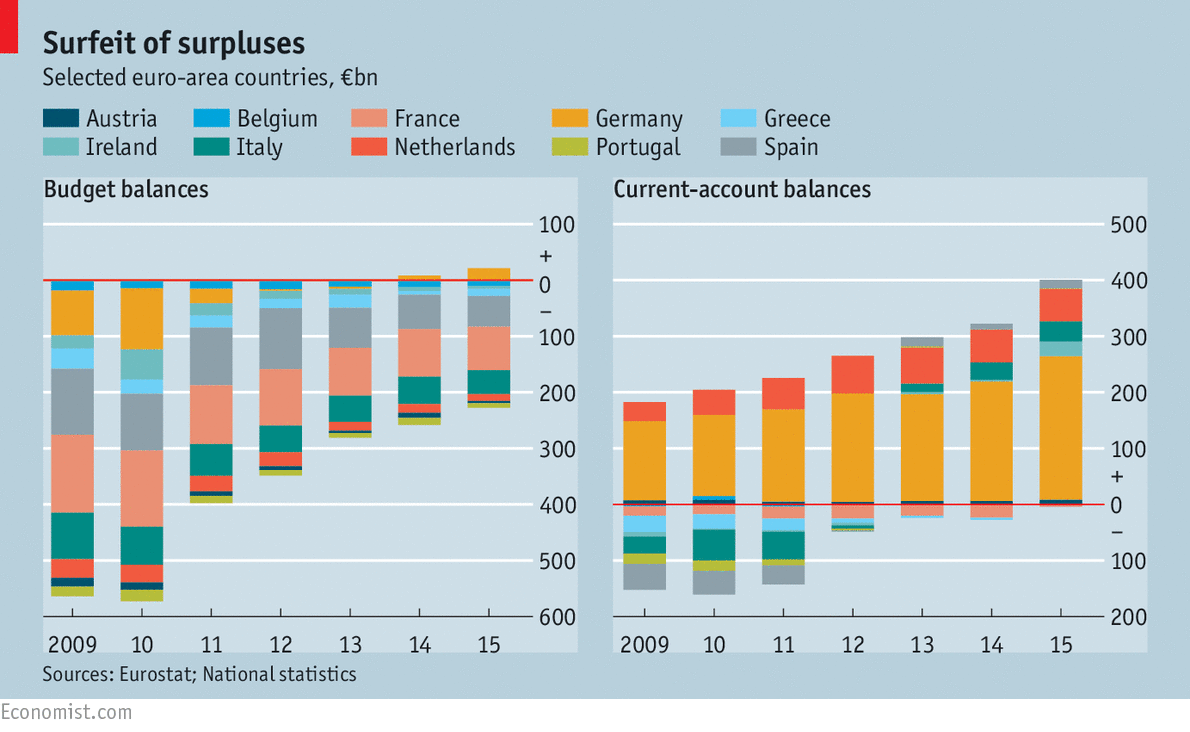

German frugality and economic woes elsewhere are linked through global trade and capital flows. In recent years, as Germany’s budget balance flipped from red to black, its current-account surplus—which reflects net cross-border flows of goods, services and investment—has soared, to nearly 9% of German GDP this year.

The connection between budgets and current accounts might not be immediately obvious. But in a series of papers published in 2011 IMF economists found evidence that cutting budget deficits is associated with reduced investment, greater saving and a shift in the current account from deficit toward surplus. Two IMF economists, John Bluedorn and Daniel Leigh, reckoned that a fiscal consolidation of one percentage point of GDP led to an improvement in the ratio of the current-account balance to GDP of 0.6 percentage points. On that reckoning, the German government’s thriftiness accounts for a small but meaningful share of its growing current-account surplus; perhaps as much as three percentage points of GDP over the past five years.

That has helped to resurrect an old problem. Global imbalances were a scourge of the world economy before the financial crisis of 2007-08. Back then, China and oil-exporting economies accounted for the surplus side of the world’s

trade ledger, which reached nearly 3% of the world’s GDP on the eve of the crisis. Other countries, notably America, ran correspondingly large current-account deficits, financed in part by flows of investment from surplus countries that flooded into the country’s overheating housing market. A similar dynamic played out in miniature within the euro area, as core economies like Germany ran current-account surpluses and peripheral countries like Spain ran deficits.

The recession that followed the crisis temporarily reduced these imbalances. Spendthrift consumers in deficit countries suddenly found themselves squeezed by joblessness and the evaporation of easy credit: that led to a collapse in imports. But a sustained era of balanced growth failed to emerge. Instead, surpluses in China and Japan rebounded. In recent years Europe has followed, thanks to a big switch from borrowing to saving (see chart). The countries on the periphery donned their sackcloth out of necessity, tightening belts and buying less from abroad than they produced at home. Ageing Europeans in core economies, like Germany and the Netherlands, saved for different reasons, such as preparing for retirement. German government-budget surpluses have piled on top of this glut.

That adds up to a big problem, given the state of the world. Within the euro area, the struggling Mediterranean economies need faster rates of GDP growth to bring down unemployment and stabilise government debt. Germany’s enormous surpluses mean that its households are buying less from other countries than they ought to. That hurts the growth prospects of the periphery, and raises the risk of a politically induced break-up.

The global picture is just as worrying. Interest rates have plunged since the financial crisis, indicating that the world’s savings are chasing too few investment opportunities. In normal times, this would be manageable. Central banks could cut their policy rates, reducing borrowing costs for firms and households and encouraging them to tap the reservoir of savings. Yet many central banks have cut rates to near zero, only to find people are still borrowing too little. As cash pours into safe assets like government bonds, demand slackens and economies stagnate.

In-the-black hole

This malaise appears to be contagious. In weak economies, battered consumers buy fewer imports and unemployment depresses wages, which can help boost exports. That provides a cushion for the suffering economy, producing a current-account surplus that siphons off spending from healthier countries. But this in turn weakens those economies, adding pressure on their central banks to cut rates. In a paper published this year Ricardo Caballero of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Emmanuel Farhi of Harvard University and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas of the University of California, Berkeley, found that in a world of integrated financial markets, a slump in some economies can eventually engulf all of them. Once a few economies become stuck in the zero-rate trap, their current-account surpluses exert a pull which threatens to drag in everyone else. America, the world’s importer of last resort, remains pinned to near-zero rates, and economically vulnerable, thanks to this dynamic.

Theoretically, this black hole can be dodged. Surplus economies like Germany just need to borrow more. Bigger budget deficits would boost global demand and reduce current-account imbalances. But Germans favour frugal budgeting. Just as important, Germany’s government, which is seen as an unforgiving taskmaster across the euro-area periphery, would prefer not to be accused of practising something different from what it preaches. And even a change of heart in Germany, helpful though that would be to the euro-area economy, would not solve everything. Imbalances are a global problem which cannot be fixed by any one country.

http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21706263-german-budget-surpluses-are-bad-global-economy-more-spend-less-thrift

"Para exportar hay que importar. Ya que exportar a crédito, genera unas deudas en los países con déficit por cuenta corriente, que al final no pueden devolver. Es como el consumo a crédito, a la qué se agota su capacidad de endeudamiento, se termina el consumo y la inversión, cae el PIB, y estalla la crisis financiera.

En la UE se han establecido unos límites de superávit comercial, para evitar los desequilibrios financieros, pongan en peligro la moneda única. Pero parece que cuesta que los alemanes dejen de ahorrar y gasten tanto como producen. Y a todo ello ahora tenemos que añadir que el Gobierno alemana está reduciendo el déficit público.

Antes del Euro, estos desequilibrios se solucionaban con devaluaciones y revalorizaciones, por lo que si los salarios de Alemania, no tienen un incremente considerable, para que se produzca una revalorización interna en Alemania, los desequilibrios financieros pueden llevar a la rotura del Euro." A.Beltran